Here’s what I watched and read last week:

Movies

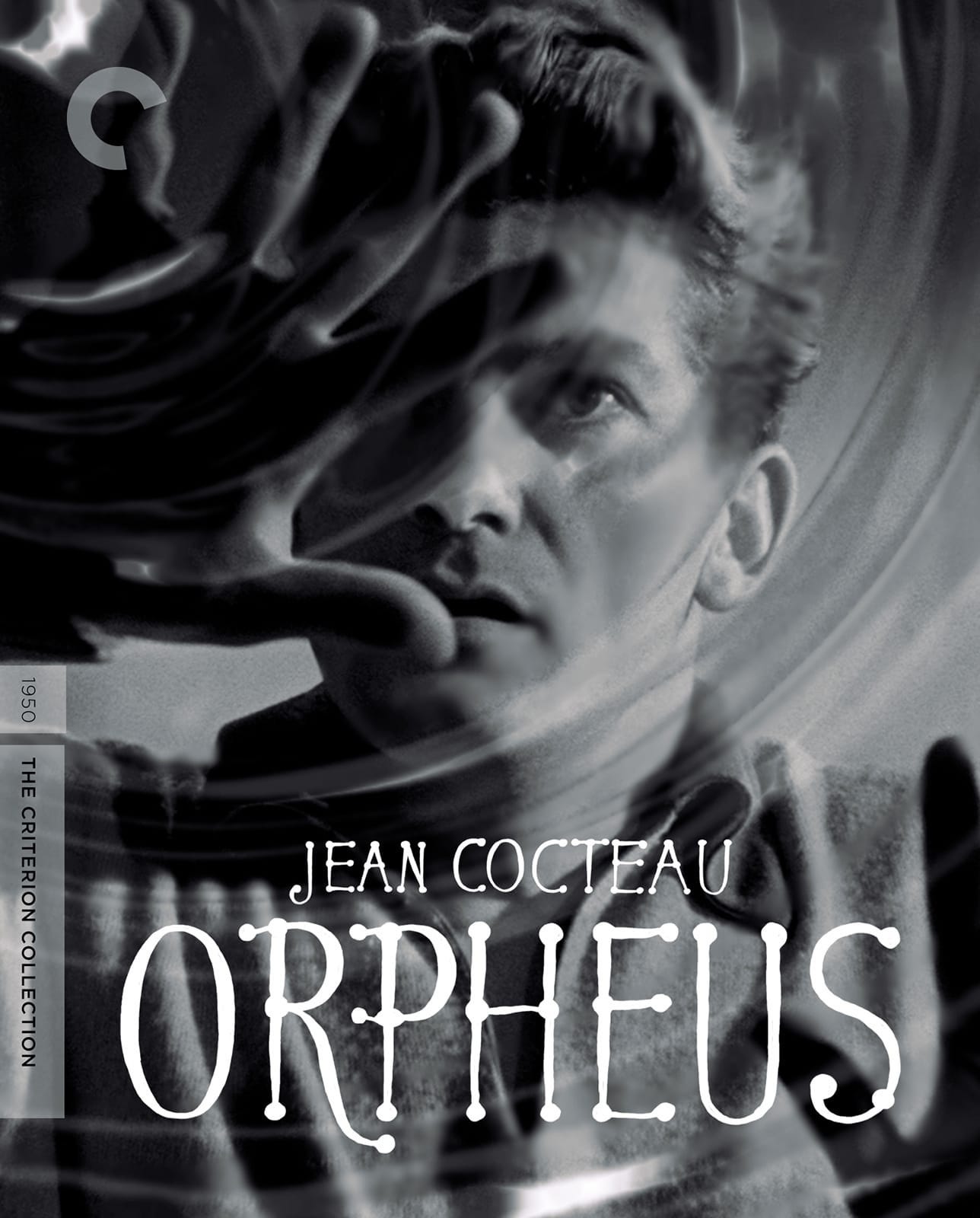

Orpheus (1950). Beautiful film by Jean Cocteau. Love the story and special effects. The underworld sequences are superb and great examples of the fantastic.

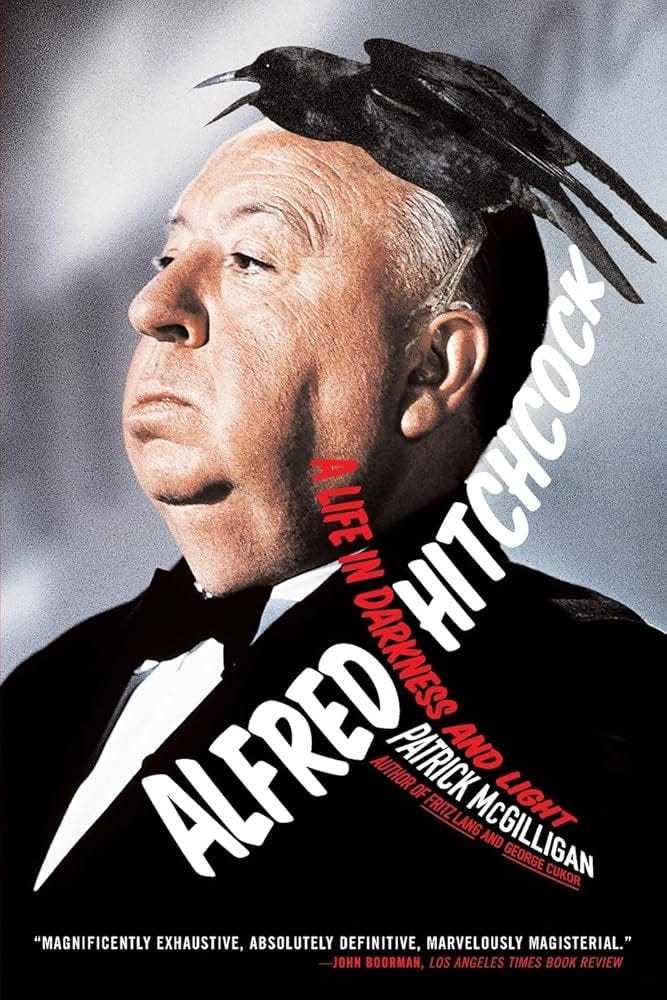

Marnie (1964). I’m starting to see why a lot fans of Hitchcock like this one - at least from what I’ve been reading. This was my third time seeing it since the early 2000s and I really enjoyed it. Marnie breaking into Rutland’s safe is classic Hitchcock and great example of his commitment to pure cinema.

Topaz (1969). The first half was very good and suspenseful, especially the opening sequence. But the second half of the film was a let down. Minor film by Hitchcock.

Broken Flowers (2005). One of my favorites of Jarmusch’s. Great and subtle performance by Bill Murray. Jeffrey Wright is so funny as Winston who does the investigating for Murray. I also love the soundtrack, which I still own on CD. Slow cinema greatness!

The Majestic (2001): Nice film. Has a kind of Frank Capra vibe. I love the way Frank Darabont captures the small town of Lawson. I also enjoyed the 1950s invasion narrative that Darabont was engaging with. Nice performance from Jim Carrey.

TV

We started the seventh season of Little House on the Prairie. Some good episodes so far. Curious to see how the characters develop. I really like the episode that featured Madeleine Stowe.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds: The first episode was a washout for me. Too much time had passed since the second season for me to remember what happened in the last episode — even with the recap. The same thing happened when I tried watching the second season of Severance — I had no idea what was going on. Overall, based on the first six episodes I’ve watched, the third season of SNW includes some questionable choices by the writers, but I’m sticking with it.

Books

Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light by Patrick McGilligan. Outstanding read. What a journey to read about Hitchcock’s life in film. I read Donald Spoto’s book on Hitchcock back in 2015. Now having read both books, I feel I have much better understanding of Hitch’s work. One of our greatest filmmakers.

Enjoying Right & Left by Todd McGowan. Excellent read. McGowan, as always, does a great job of explaining the concepts - focusing on the differences between belonging and nonbelonging and their relationship to enjoyment. McGowan offers lots of great examples to explain how the right and left organize enjoyment and the important role of contradiction. I love the chapter on Christmas movies and the last chapter on Heathers.