Happy New Year!

I’m happy to announce that my new novel, My Lovely Dark Summer, is now available for pre-order.

A big thank you to Lynda at Easy Reader Editing for her excellent copy editing. I also designed the cover for this one.

This is a young adult novel with sci-fi elements set in 1994. I was inspired by a YouTube video about an abandoned highway that was once planned in Connecticut. I had so much fun writing the story, and I hope you’ll check it out.

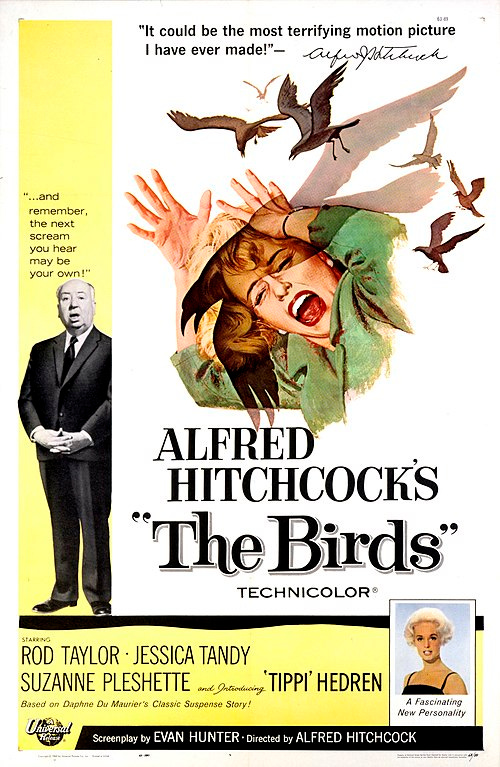

Hitchcock Project update. I have written five chapters and am about halfway finished with the conclusion. I’ve already completed a close edit of the introduction and chapters one and two. The proposal is almost done, and I may begin sending it out in February or March. Hopefully, the next newsletter will include some good news.

Run to the Future. This is the second Charlie One book I wrote last year. I am currently editing the third draft and think it could be ready by spring 2027.

Books read and currently reading. I’ve been reading extensively on Lacanian and Freudian psychoanalytic theory. This has been my area of study since 2005, when I was a graduate student at the University of Vermont. There is still so much to learn.

You can always see what I’ve been watching and reading by subscribing to my Substack page or checking out my blog.

Well, that’s it for me.

Enjoy the winter.

Keep reading. Watch movies.

Tom C.