The photos narrate the experiences of Mod youth Jimmy in 1964. The images reflect the ephemeral and fleeting nature of Jimmy's memories.

About Me

- Tom Connelly

- Thank you for visiting my blog. I’m a scholar of television, film, and digital media, and the author of CINEMA OF CONFINEMENT (Northwestern University Press) and CAPTURING DIGITAL MEDIA (Bloomsbury Academic). I’ve published a variety of articles on film and television in journals published by Taylor & Francis. I am also a writer of fiction. All of my books can be viewed on www.tomconnellyfiction.com

Saturday, August 4, 2012

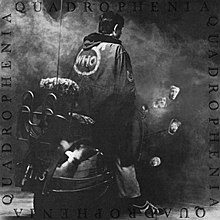

The Postcard Book Trailer and Thoughts on Quadrophenia

The photos narrate the experiences of Mod youth Jimmy in 1964. The images reflect the ephemeral and fleeting nature of Jimmy's memories.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

All Out War - Sum of All Fears - 1992 Demo Release - Hardcore

Sunday, July 31, 2011

The Aging Movie Star in the Horror and Sci-Fi Genres

Consider the movie Them! (1954) one of the first atomic-age monster films, which casts aging star Edmund Gwenn as Doctor Harold Medford, an entomologist, who discovers that the mutant ants are powerless without their antennae. Even though the scientific discourse in the film seems be a bit obvious, the knowledge of the mutant has to pass through Medford as the figure of knowledge to legitimatize it's narrative exposition.

In the 1970s and 1980s, there seemed to be a plethora of horror/sci-fi films with the aging star as the figure of knowledge and reason. For example, John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) starred Donald Pleasence as Dr. Samuel Loomis, Michael Myers' psychiatrist. It is Dr. Loomis who knows Michael's condition and intentions that he will kill his sister and believes he is the only one knows how to stop him.

In David Cronenberg's The Dead Zone (1983), Herbert Lom plays neurologist Dr. Sam Weizak as the figure of the older erudite man who provides knowledge to viewers about Johnny Smith's (Christopher Walken) power of seeing a person's future through physical contact.

As a side note: The Dead Zone has a fantastic and creepy opening credit sequence where the lettering of the title's typography slowly appears on the screen over images of the town of Castle Rock, Maine. Here the title sequence emphasize the letters' negative space, which reflects the concept of "the dead zone," a void in the future that Johnny cannot predict-such as the ending of the film.

We also find the casting of the aging actor as the conveyer of knowledge in fantasy/science fiction films. Most famous is the casting of Sir Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan "Ben" Kenobi in Star Wars (1977). Ben plays the figure of the aging Jedi Knight who explains to young Luke about Darth Vader and the Clone Wars.

Even the political sci-fi thriller Children of Men (2006) casts Michael Caine as an aging hippie cartoonist, Jasper Palmer. Palmer as the conveyer of knowledge and comic relief helps propose the plan for Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) and Theo Faron's (Clive Barker) escape.

As such, the icon of the aging star plays an important function in the sci-fi, fantasy, and horror genres as the communicator of knowledge, wisdom and reason.

The role of the aging star actor also raises the question of science fiction and horror films as occupying a B-film status. Certainly many sci-fi, superhero and horror films are produced with high quality, especially given the power of today's special effects. And many of these fables and story worlds are well written, and inform us about our own experiences of everyday life on planet earth.

But given that the overall body of work of these older actors is not often associated with fantasy and horror films suggests how the presence of an aging star can help legitimize a film's exploration of topics such as mutant bugs, telepathy, monsters, and other forces beyond the everyday world.

Thursday, March 10, 2011

The Velocity of the Long Take

As early cinema developed out of the period of the actuality film and cinema of attractions, and into a narrator system linked to the emerging Hollywood studio, we begin to see the structuring and standardization of filmic space and temporality. This unification of cinematic time and space, according to the research done by Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson came about through the melding of various modes of practices such as division of labor and agreed upon set of stylistic norms on how movies should properly tell a story. In their research, shot duration, in particular, plays an important role in sustaining the realist illusion of narrative time and space. Bordwell et al. note that the majority of Hollywood films (during the classical period) did not exploit short or long takes as a means of narration in order to prevent viewer from becoming aware of the film’s construction of time and space.

But if the management of shot length is to prevent viewers from becoming aware of the apparatuses that create a film’s virtual world, how do we account for the long take that evokes a sense of speed and can even further the experience of narrative immersion? Using the long take as a form of speed, I argue that there is no necessary correspondence or a strict one to one relationship between shot duration, viewership and the concealment of the construction of filmic time and space. This is not to suggest that long takes are not used to disrupt or engage with temporal and spatial continuity in order to evoke perceptions of slowness or contemplation. This style of filmmaking is evident in the works of Gus Van Sant, Bela Tarr and Michelangelo Antonioni, who employ long takes as a means to create a cinema of duration and stillness alternative to traditional narratives.

The first half of this presentation, I will show some examples of the long take as a form of speed and how these directors and their production crew negotiate and push the limits of the latest technologies to meet their visions. And the second half of the presentation will tackle the theoretical question of shot duration in regards to defining the essence of cinema.

I would like to begin with an example from Joseph H. Lewis’ crime drama, Gun Crazy (1950). The long take we are seeing involves a bank heist, which takes place from the point of view of outlaw and thieves Bart and Annie played by John Dall and Peggy Cummins. To create the sequence, Lewis used a stretch Cadillac and removed all the seats to fit the camera operator and a bare bones production crew. Instead of following the script, Lewis had both actors Dahl and Cummins improvise their dialogue to enhance the suspense and realism of the scene.

Lewis stated that the scene was so real that “Off-screen there were people that yelled, ‘They held up the bank, they held up the bank,’ … none of the bystanders [of the town] knew what we were doing. We had no extras except the people the policeman directed. Everything—cars, people—was there on the street” (47). Thus, the Hampton robbery scene illustrates that the long take not only can be re-purposed to create a feeling of immersion and suspense, but also can invoke a sense of speed and velocity.

The desire to move the camera and to create a dynamic cinematic space can be traced back to the silent film period. In Lotte Eisner’s book on German film director and expressionistic pioneer F.W. Murnau, she refers to notes typed by Murnau in which he expresses a wish from “Father Christmas [to create] a camera that can move freely in space” (84). Murnau’s wish would practically come true in the 1970s with Garrett Brown’s invention of the steadicam. Handheld photography had already established itself as a style employed by narrative filmmakers and documentarians. But the Steadicam not only can track its subject with fluidity, but it also run within the profilmic space without the camera obtrusively bouncing up and down. Let’s take a look at the Steadicam in action.

Today, with the emergence of state of the art simulation technologies, films now can incorporate many layers blended together within the frame such as virtual actors, crowd sequences and matted paintings with live action recording. More so, as Lev Manovich notes, “Digital compositing does represent a new step in the history of visual simulation because it allows the creation of moving images of non-existent worlds” (153 Authors emphasis).

Conversely, the impression of slowness or fastness does not always have to entail long takes. Films that use the standard methods of editing can also disrupt the transparency and unity of cinematic time and space through the elements within the frame itself.

D. N. Rodowick makes a similar argument in his critique of Russian Ark (2002), a film shot in one long take using digital technologies. He notes “The key to resolving the discrepancy between Russian Ark’s self-presentation and its ontological expression as digital cinema is to understand that it is a montage work, no less complex in this respect than Sergei Eisenstein’s 1927 film October” (165).

What I think it is important to point out in these theoretical debates in regards to editing and shot duration is not who has the stronger or better argument in terms of defining the essence of cinema, but the tension that has emerged in regards to its very definition. Here, I draw upon Stuart Hall’s model of articulation which entails how the production and consumption of cultural objects are represented and negotiated within the lived practices of every day life.

To conclude, as I hope to have shown, the ordering of cinematic time and space is not directly tied to a hegemonic mode of production, or linked to a grand essence of cinema. In these examples, we have seen how artists mold the current film technologies to meet their story visions. And we have also seen how the orchestration of the elements within the frame can distort normal pictorial time and space as was the case with Lynch’s Fire Walk with Me. Thus, these examples provide a glimpse into how much information is at work in creating a film’s story world (whether its traditional film photography or digital technologies), and how they can potentially create impressions of speed in relation to the construction of cinematic time and space.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

The Workings of Time and Space in the Paintings of Archibald Motley

Archibald F. Motley’s painting After Fiesta, Remorse, Siesta, is a beautiful visualization of jazz.

Motley uses dichotomies within this painting to create an ethereal feeling For example, he contrasts the woman at the piano with a portrait on the wall of a matador fighting a bull—suggesting a masculine/feminine dichotomy. In the background, a couple is embracing by a street lamp. In the far corners of the lamp post are the dangerous cactus and the soothing palm tree, adding to the abstract and surreal feeling of the image.

The crowding of images in the foreground while leaving open space in the background is another motif of Motley’s work. Motley positions the patrons who are having a good time in the foreground, very close to one another. The lonely or aloof figures are positioned in the background.

For example, in the painting Barbecue, the patrons are having a good time at the tables in the foreground. In the background, the space is more open and only a few patrons dance. Also framed near the fence in the far distance is a man, alone, looking down with his hands in his pocket.

Motley positions the aloof characters so it takes time for the eye to recognize them in the painting's space. Because the eye is not quickly drawn to the lonely man in Barbecue, the painting suggests that the patrons do not recognize this man. The man is not only absent from their enjoyment, but seems to be unstuck from the painting's time and space.

Similarly, in After Fiesta, Remorse, Siesta unexpectedly to the right center is a man asleep with his head in his hands. Once the eye catches this man, one has to rethink the time and space of the painting. Did this mysterious man’s attempt to meet a woman prove futile? Or are what we are seeing in the painting is his actual dream?

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Movie Posters Better Than The Actual Movie

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Ronald D. Moore - The Bonding

I recently watched a Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) episode called "The Bonding," which was penned by Battlestar Galactica (2004 series) creator Ronald D. Moore. "The Bonding" was Moore's spec script he wrote in 1988. The history behind the script is that Moore was on tour of the Paramount studio where they filmed Star Trek. Moore showed the script to the show's creator Gene Roddenberry's assistant, who liked it and was able to get Moore an agent.

"The Bonding" eventually made its way to Michael Piller (who had been promoted to lead writer of the third season). Piller purchased the script and the episode aired during the show's third season on October 23, 1989. I believe that Moore's introduction into Star Trek not only helped the show's transformation, but is an example of fandom writing that finds its way into prime time TV. Moreover, "The Bonding" is an early example of what is now commonly referred to as the re-imagining of a previous TV show or movie.

Before Piller was promoted to lead writer, the original ST and the first two seasons of TNG were primarily "alien of the week" situations. Though many of the "alien of the week" scenarios were great episodes, TNG, arguably, had no clear identity. During the third season, however, the themes of the episodes gradually turned inward, developing deeper characterization to reflect the inner-selves of the crew of the Enterprise. During the third season would begin to form TNG's identity. "The Bonding" would play an important role in the series transformation.

The episode centers on the story of a young boy named Jeremy Aster, who's mother (Lt. Marsah Aster) is unexpectedly killed on a scientific mission. Worf, who was apart of the mission, is upset about Marsha's death because it reminds him of the passing of his own parents. Jeremy and Worf come together through a Klingon ritual called the R'uustai - a bonding where the two become brothers.

One can think of textual poaching as readers who rent spaces, but never fixed in one location. But whereas de Certeau interprets poaching as a tacit and lone process of appropriation, Jenkins extends the concept of textual poaching into the world of fandom, where fans' expression is outwardly projected such as attending conferences or sharing information on the web.

The story of "The Bonding" retains the integrity and history of the Star Trek series as well as re-imagining new ideas within that world. That is, Moore expands and renews the traits and identities of characters already established by previous ST writers while giving them more depth and complexity. For example, Moore creates a character arc for Worf by introducing the backstory of Worf''s father's honor who had been rejected by the Klingon's. A story that would further develop in the 4th and 5th season. Moreover, "The Bonding" contains themes that Moore would fully explore in Battlestar Galactica such as honor, loyalty and solidarity.

Watched and Read - January 18, 2026

Here's what I watched and read last week... MOVIES La La Land (2016), directed by Damien Chazelle , is a masterpiece. It is not only...

-

When I first taught world cinema, I knew I wanted to assign Ingmar Bergman 's The Seventh Seal (1957). But when the time came to put my...

-

The Lacanian gaze is one of the hardest concepts I teach for my Film Theory course . The way we commonly think of the gaze (to look) is not...

-

I often teach Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974) for my Introduction to Film and Film Theory courses. The Conver...